General Pershing’s Telephone Operators Receive Their Medals

This was written by John Motheral, editor of the Fort Point Salvo, the newsletter of the Fort Point and Army Museum Association. Volume 4, number 6, December, 1979.

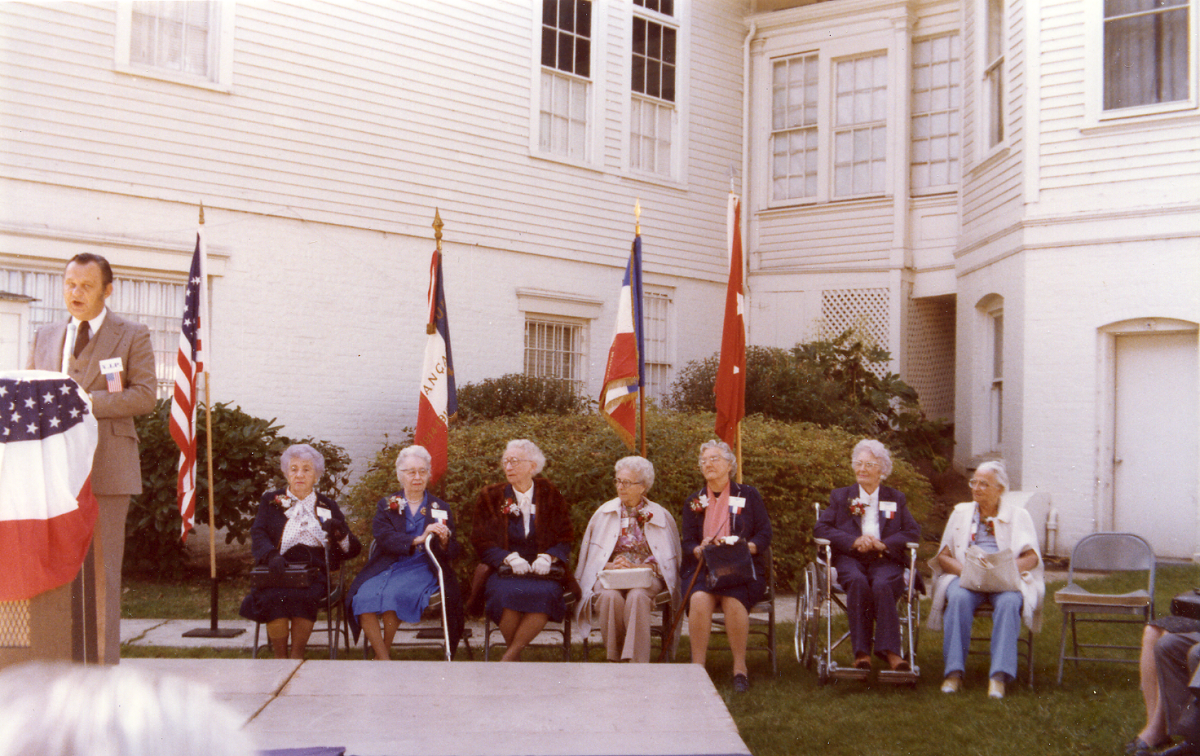

“J’Ecoute” (“I am listening”, the French equivalent of “Number please”) echoed from the Presidio Army Museum on Veteran’s Day, November 11, the 61st anniversary of our victory in World War I. It also marked final victory in the 60-year campaign by General Pershing’s French-speaking telephone operators for recognition as the soldiers they certainly were, and for attainment of full veteran’s status and benefits. Led by Mrs. Louise LeBreton Maxwell of Berkeley and Mrs. Marie Lange Harris of San Francisco, seven of the surv1vmg Bay Area members of the Women’s Signal Corps Telephone Operators’ Unit, which numbered about 300 overseas in 1918, were Veteran’s Day guests of honor at the Presidio of San Francisco. In addition to Mrs. Maxwell and Mrs. Harris, the ladies were: Mrs. Helen Hill Verdi of Berkeley, Mrs. Raymonde LeBreton Galet of San Carlos, Mrs. Maude Johnson Webster of San Jose, Mrs. Bertha Plamondon Dubsky of San Francisco and Mrs. Cordelia Dupuis Davis of Covina.

More than 500 came to see them have their World War I victory medals pinned on by Colonel George Pappas (Ret.), past president of the Company of Military Historians, and help them open their exhibit named “J’Ecoute”, a gallery full of treasures from their “Great Adventure”.

All the ladies are nearly 80 or past it now, but they brought to the Army Museum the same charm and verve that led them as girls in their late teens and early 20’s to set aside schools, jobs, whatever they were doing. Go through a crash course in switchboard operation given by Pacific Telephone here and by American Telephone and Telegraph in New York. Pay for their own uniforms. Trade lingerie for long flannel nightgowns and heavy woolen stockings. And sail for France across a submarine-infested ocean to handle the vital flow of communications for an Army that knew little or no French. They kept the lines of the A.E.F. open - some of them at the front, and to the very last moment when their telephone shacks burned down around them.

Honors at Last

Mr. J. D. Rizo, Pacific Telephone Executive and President of the Telephone Pioneers, opened the ceremonies. The seven veterans of the telephone “fighting lines” and all who had come to join them on the Museum’s sunny lawn were welcomed by Colonel F. Whitney Hall, Jr., Post Commander of the Presidio of San Francisco.

The Honorable M. Thiollier Jean-Francois, Vice Consul of France, came to thank General Pershing’s “Hello Girls” personally and to speak of friendship, too. The friendship of two strong nations which often differ, but stand together in the flames of crisis.

General Sniffin Tells the Story

Major General Charles R Sniffin, Deputy Commanding General, Sixth United States Army, told the story of the Women’s Telephone Unit’s long wait for recognition:

“Today, you know, marks the 61st anniversary of the silencing of the ‘Guns of August’. “The hostilities which began in the summer of 1914 were suspended at the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918.

“At that war’s end, General John J. Pershing said to the men of his American Expeditionary Force, ‘The enemy has capitulated. It is fitting that I address myself in thanks directly to the officers and soldiers of the American Expeditionary Forces who, by their heroic efforts have made possible this glorious result” ...

“You’ll notice that I said General Pershing spoke to his ‘men’. That’s because officially there were no American women serving in the Armed Forces of that day and were it not for the action of the Women’s Overseas Service League, and the passage of the G. I. Bill Improvement Act recently, the services of a small but important group of volunteer women might have gone unnoticed and unremembered. A few of the original members of a special Signal Corps unit are with us today to help us honor and celebrate theirs and others’ experiences. It was ‘Blackjack’ Pershing, himself once a resident of this Post, who requested that the special unit be formed of French-speaking women telephone operators in order to assist the A.E.F. ‘s communications network ...”

They were hired as civilians, since no law at the time enabled them to enlist in the Army. In March of 1918, a large portion of that group sailed for Europe where most of the women worked until June of the following year, after the Armistice. Finally, last May, the Department of Defense determined that the volunteer members had indeed performed military service and that they were entitled to the full benefits afforded any military veteran for honorable service.” Mrs. Maxwell said with a laugh, “We always knew we were in the Army. It just took them 60 years to admit it.”

J’Ecoute Exhibit on Display through February 1980

After the ceremony, the ladies trooped up to the Museum’s large exhibit gallery. They helped General Sniffin cut the ribbon across the entrance and the crowd poured into the J’Ecoute exhibit.

It is the telephone girls “Great Adventure” relived. A gallery filled with wonderful photographs, letters, press clippings, albums, insignia little known today, switchboard equipment, a complete Signal Corps telephone operator’s uniform, probably one of the two or three still in existence. And a World War I switchboard loaned by Pacific Telephone.

The gallery rocked as acquaintances were renewed, stories told and retold in French and English, experiences shared with other veterans of World War I. As the Museum closed for the afternoon everyone agreed that General Pershing’s women telephone veterans fit to a “tee” the line in Mary Martin’s play “Valentine” - these “old people are just young people who have lived longer”.

“I have no sons to Give to France, so I send her my Daughters!”

Mme. Jeanne LeBreton murmured those words as she waved good-bye to her daughters, Louise 19 and younger Raymonde, leaving on the Sunset Limited for New York - and France, February 12, 1918. They and six other girls made up the first local contingent to answer General John J. Pershing’s call for American telephone operators, fluent in French, to man the switchboards of the A.E.F.

Louise Le Breton, 19, first Bay Area volunteer in Women’s Signal Corps Telephone Unit sails for France, March 1918

When he arrived in France in June 1917 the General found the French telephone system in shambles after three years of war. He decided an extensive American system would have to be built covering an area from the French ports of Le Havre, Brest, St. Nazaire and Bordeaux to Paris, to Tours, (Headquarters of Service of Supply), to Chaumont, Haute Marne, (A.E.F. Headquarters). And from there to the fronts where the American soldiers would be fighting.

Consequently, the first troops ordered to France in July 1917 were Signal Corps Battalions. And how they worked! In less than four months, by November, General Pershing was able to call for enlistment into the Army of 200 French-speaking, American-trained telephone operators. They played a key role providing dependable French-English communications which were vital to the prosecution of the war.

Louise LeBreton was the first girl in this area to enlist. Her sister, Raymonde, the second. “For one thing,” says Louise, “after the agony General Pershing went through when his wife and daughters were burned to death in San Francisco, I always felt he belonged to me. I wanted to take care of him any way I could.”

The Great Adventure

This is the story of the “Great Adventure” of Louise Le Breton, now Mrs. John K. Maxwell of Berkeley:

“My younger sister, Raymonde and I had been in this country four years. We had been in school in France before that time, and when we read the recruiting article in the papers we decided to send an application to Washington, without telling our mother, who, we were sure, would give us a categorical “NO”. We waited. with anxiety for a reply but none came. Christmas came and went and the New Year and still no answer. So, we went about our business and forgot about it. Then on Jan. 8, 1918, we each received a telegram requesting us to report to an official of the Pacific Telephone and Telegraph Co. in San Francisco for an interview. It must have been favorable for on January 19, we received another telegram instructing us to report to the same official for temporary duty.

We had to overcome our mother’s reluctance to let us go and finally, after a visit with Mr. Hamm of the Telephone Co. who assured her we would be billeted with French families and would not be in the danger zone., she gave her consent.

“There followed intensive training at the San Francisco Telephone School for two weeks on local and long-distance boards and a few days of actual operating at a small office in Richmond. After a complete physical examination, vaccination and inoculation we took the Oath of Allegiance here at the Presidio of San Francisco and were sworn into the Army…

“On Feb. 12, we boarded the Sunset Limited. A week later we were in New York, in hotels, reporting each day to the American Telephone & Telegraph offices, 195 Broadway, for further training, being outfitted with uniforms, purchasing high laced shoes, blouses, warm underwear, overseas caps and dress hat ... Then we were told to send our civilian clothes back home.

Convoyed across the Atlantic

“And so, the First Unit of Telephone Operators composed of 33 young women from all over the country received orders, Feb. 23, 1918 to proceed to Hoboken, New Jersey where we awaited transportation to France. We were billeted in a former bar, 35 Army cots alongside each other, one suitcase apiece and one Army locker, ready to embark. At last, on March 6, at 5 a. m., we were awakened and told to get ready. A half hour later, carrying our suitcases, we were marched to the old White Star Liner, Celtic, now a converted troop ship. She was beautifully camouflaged. We were ushered immediately below decks, assigned to our cabins and told to remain there until the ship was out of the harbor. We sailed at 6 a.m. very silently and stealthily. The port holes were covered with black curtains so we couldn’t even see the Statue of Liberty when we went by.

“We met our convoy at Halifax. The Bay was still ice bound with big blocks of ice breaking up, and for California eyes this was a fascinating and awesome sight. There were about 12 ships in the convoy, accompanied by two destroyers. “We began zigzagging in the submarine danger zone and for three nights slept in our clothes. We were kept busy with life-boat drills, French conversation for the benefit of the officers on board. The hardest part was the roll-call on deck at 7 a.m., all dressed for the day, and twice at dawn for burial at sea of soldiers who had died of ‘flu’.

Perfect U-Boat Target

“On the 12th day as we were approaching Liverpool, our ship struck a sand bar. One of the destroyers attempted to pull us off but the cable snapped and so we remained there one whole moonlit night, a perfect target for submarines. The convoy went ahead, one destroyer remaining with us. As the tide changed the next morning we could proceed to Liverpool. From Liverpool to London and then to Southampton for a week, adjusting to war-time rations, saccharine instead of sugar, roasted barley instead of coffee, and no sweets to be had at any price. Two whole days on a little Channel packet, caught in a dense fog between Southampton and Le Havre and running into a submarine net, and narrowly missing being rammed by a French cruiser.

“Pauvres Refugies”

“Paris at last after a long, long ride from Le Havre. A Signal Corps Captain met us and marched us to the Y.W.C.A. ‘Hotel Petrograd’. We each had a heavy suitcase to carry and in the dim blue lights of the streets we could hardly see the curbstones. People passed us in the darkness: ‘Pauvres refugies’ (poor refugees), they said. Midnight and sleep at last only to be awakened by an ALERTE and urged down to the first floor for safety. “ In Paris we were divided into three groups, one to be stationed at Tours, Headquarters of the Service of Supplies, one to remain in Paris, and the third to go to Chaumont-Sur-Marne, General Pershing’s Headquarters with Miss Banker, our Chief Operator. I was among the latter, while my sister had been assigned to Tours.

“Hello Girls”

“Everywhere we were received by officers and men with happy smiles. The day after our arrival in Paris a reporter for ‘The Stars and Stripes’ with a good sense of humor, wrote the following:

‘HELLO GIRLS HERE IN REAL ARMY DUDS-- Signal Corps colors adorn hats of new bilingual wire experts. They have Sergeants, too. Company of 33 regulars represents half the States of the Union. Uncle Sam presents HELLO GIRLS!

A melodious, mirthful extravaganza in three coils, produced for the first time in France, under the auspices of the A.E.F.

Protective and benevolent society for the suppression of Huns in the Theatre de Guerre. Performances in both French and English. Assisted by a chorus of 33 REAL AMERICAN TELEPHONE GIRLS - COUNT THEM - 33 able to get anybody’s number the first time - including THE KAISER’S.’

“One girl reported that when she plugged in and answered her first call saying NUMBER PLEASE, the voice at the other end of the line exploded with ‘Thank, God!’ - everyone in the office laughing including the operator.

“In Chaumont, the office was in the stone military barracks called the Caserne, a small room on the first floor. Those barracks had once been the Headquarters of the Russian Imperial Army in France. Now they were General Pershing’s Headquarters.

“This is where I was generally assigned to handle the French calls. We had been there about two weeks when I was assigned to our third local Board. On that Board General Pershing’s personal telephone showed in red and we had been told that whenever that light came on, we were to drop everything, disconnect anyone, and answer it within a half second.

Never-to-be-Forgotten, 9:20 a.m.

“Well, for the first time in two weeks the light appeared. My cords were all in use. I never knew who it was I disconnected, but I plugged in breathlessly with ‘Number, please’ expecting a call to the President of France, or the Chief of Staff or Marshal Foch. The voice at the other end responded: ‘What time is it, operator?’ No one had asked me for the time before and I stammered with great surprise: ‘I beg your pardon, Sir!’ ‘Operator, this is General Pershing. What time is it,

please?’ I looked at the clock over the door. ‘It is 9:20, Sir!’ What a come down! I took a deep breath, turned toward Miss Banker, our C.O. and said loudly: ‘General Pershing just asked me for the time!’

“Well, if a bomb had fallen in the office there couldn’t have been more of a commotion. C.O. and supervisors came running, my headset was removed, and with a ‘Follow me, Miss Le Breton’ I was taken to our rest room where I was sternly reprimanded for disturbing the office in such a manner, and told that if General Pershing were in residence our office would have been notified, ... in other words, she didn’t believe me. But I still insisted: ‘Miss Banker, he did ask me for the time!’ With ‘Miss Le Breton, you are confined to quarters for 30 days’ she walked out, very angry. The next day an aide called to say that General Pershing was coming on a tour of inspection. “As he went through the office he turned to Miss Banker and said: ‘By the way, one of your efficient operators gave me the time yesterday morning.’ “Miss Banker admitted she had been hasty but I was still confined to quarters for a week. Military discipline had to be maintained.

American Bow-Wow

“As the weeks went by we were conscious that preparations were being made for an offensive. We began having code names and direct lines to Podunk, Mohawk, Waterfall, Widewing, Flying Fish, etc. We had two recording operators and the supervisors brought us the tickets of the calls to be made over the long-distance lines. One day some tickets were brought to me and among them a call to an officer at ‘American Bow-Wow!’ I had no Bow-Wow on my list of codes. I called the code office. No record. I then called the officer who had placed the call and told him we had no such place as ‘American Bow-Wow’. He laughed heartily and with a nice southern drawl said: ‘I called Lignyen-Barrois’. The Barrois sounded like Bow-Wow.

The President of France on Tip-Toe

“Another fond memory of Chaumont was on August 6, 1918, when the President of France, Raymond Poincarre, came for a short visit to bestow the Grand Cross of the Legion of Honor on General Pershing. We, the operators not on the Boards, and the entire headquarters personnel, consisting of several hundred men and women, turned out to witness the proceedings, all standing at attention. After Monsieur Poincarre had pinned 0n the Cross, he rose on his tiptoes, as he was a short man, to kiss General Pershing on both cheeks according to French custom. And our General, over six feet, had to lean way down. It was so very comical, we had a hard time restraining our, giggles. In his Memoirs, General Pershing says:

‘Without implying the slightest criticism of the form of salutation used in the ceremony, I cannot refrain from confessing my embarrassment, especially as I could hear the restrained laughter of the irreverent Americans in the area who witnessed my situation ... I thought that M. Poincarre himself was quite as much embarrassed as I was. Moreover, he must have heard the suppressed mirth as plainly as I did.’ “On Aug. 25, 1918, I received a promotion to the rank of supervisor, and was told to pack my belongings, that I was being transferred to Neufchateau in the Vosges, to the headquarters of the First Army and the Advance Section of the Service of Supplies, and that my sister was to join me. For this, I was very pleased.

Neufchateau and the Angry Sergeant

“Neufchateau was different. What a contrast! A town at war, the hub of many roads, bivouacs in the fields everywhere, troops being moved toward the Front in every type of available vehicle, driven at night, without lights. The St. Mihiel Drive was being prepared, the telephone office swamped with calls, new camp boards being installed, stepping over wires continuously, no provisions made to house Signal Corps women, some of us in hotels, others sharing rooms in private homes, many times cooking our own meals after a strenuous· day of work.

“One morning the Chief Signal Officer came to the office accompanied by a young Sergeant and said: ‘Miss Le Breton, this is Sergeant Maxwell, a traffic expert, who has been sent to help us. He will have many questions to ask.’ The tight-lipped Sergeant looked around, asked no questions, and disappeared. In about three days, the Telephone Office was reorganized, new boards were installed and telephone traffic ran smoothly. “As I became a little more acquainted with our Traffic Sergeant, I found out that he was a very angry young man. He had enlisted in Philadelphia, was sent over immediately with the 406th Telegraph Battalion in July 191 7, had put up poles and strung wires. Someone found out he was a former Traffic Man and had him transferred out and put in charge of WOMEN! I think, I then unconsciously began a campaign of my own to show him that we were not so bad. That we were soldiers, too!

Lines Never Failed at St. Mihiel

“On Sept. 12, 1918, the attack on the St. Mihiel Salient took place, a definite victory for our troops. We were proud of our contribution in keeping the lines open to all calls. Men’s lives depended on them.

“I would like to give you a little sample of the calls which came through to us. Although we were told not to keep a diary in case it fell into enemy hands, one of us, also from Berkeley, Mrs. Bertha Hunt, kept a very small one:

‘Bombing was bad up Santiago way. Bombs burst in next room to operator and finally took the roof right off and knocked things about a bit. It was terribly busy for us, and hard, too, as the lines were bad on account of bombing. Report on one line was ‘Out of order from hand grenade,’ - another: ‘Out of order, a cow scratched her back on the pole!’ We also delivered messages: For -instance, this cryptic one: XX Company found way out of difficulty and will be towed in.’ Message from French Central: An American Adjutant in a French hospital was well enough to be moved to American hospital. What to do with him? No one in hospital at Bazoilles could speak French, so by staying on the line and translating we were able to get him transferred.’ “It was not always this dramatic, though. For instance: At noon, an outside trunk came in for a French call and as he couldn’t speak French, and I was not too busy, I camped on the French line with him. He got an idea of what must be done and was very grateful and most profuse in thanks, said he would do something for me sometime. He was at the meat commissary. I said jokingly, ‘Send us some beefsteaks.’ Next day nine of the finest filets ever arrived.

‘What dya Mean J’ecoute!

“Miss Banker and five operators had been transferred to the Advance Section of the First Army, first at Ligny-en-Barrois, then at Souilly. One evening, Miss Hill, who is now Mrs. Verdi, and lives in Berkeley, asked permission to go to the office to put in a call to one of the operators in Paris. My Chief asked me to accompany her. Three men from the Signal Corp were operating the Boards. They were alight with lights. While Miss Hill was putting in her call, I put on a headset and began making connections. Corporal Whiting, sitting next to me, nudged me and said: ‘French call’. I plugged in and said in French: J’ecoute - the French equivalent of ‘Number, please’.

An irascible voice answered me: ‘What do you mean, J’ecoute? I want THE FIRST ECHELON, ADVANCE HEADQUARTERS OF THESE HEADQUARTERS.’ As our headquarters changed every night during the St. Mihiel offensive, I answered: Yes, Sir. Where is the First Echelon located, Sir? ‘You know very well where it’s located, operator’. No, Sir. We are not given that information, Sir. ‘What is your name, operator?’ I am not allowed to give you my name, Sir. My number is Operator 22. ‘Operator, I am in command of this post tonight, and I demand that you give me your name.’ I am sorry, Sir, but I cannot do it. I am Operator 22. ‘Let me talk to the man I first talked to.’ Corporal Whiting had been listening and repeated everything I had said. The next morning the Chief Signal Officer called me in his office and informed me that Corporal Whiting and I were to appear before a Court Martial that very day for insubordination and refusal to obey a command. When I explained what had happened, the C.O. said, ‘You were absolutely right and you have nothing-to fear… The Colonel who placed the call heard us calling Ligny-en-Barrois over the French lines, and also our code name for Ligny, Waterfall, and took it for granted that we knew. We only learned this after the Armistice.

Operators to the Front for the Meuse-Argonne

“We were all envious of the girls, seven of them, who went with Miss Banker to the Advance Section of the First Army. They were so near the Front and operated the Boards with their gas masks hanging in back of their chairs. Miss Hunt was one of them. I read from her diary: Sept. 30 - Had a call over the wire to a Chief of Staff regarding a message brought by carrier pigeon.’ The pigeon was from the Lost Battalion. (Ed. note: One of the bravest fighting forces the world has ever seen.)

“Three or four months after our return home, the War Department send us numbered lists of pictures taken of our Signal Corps barracks and asked us to check which ones we wanted. I checked several, one of them of our room in the barracks at Neufchateau. When the pictures arrived, to my surprise, mine turned out to be two soldiers, one of them holding a pigeon. There were some 10,000 carrier pigeons being used and it is stated officially that 95% of the messages carried by pigeons were delivered, including this one, that read ‘take it away; I’m tired to carrying this damned bird.’ “We were terribly busy during the Meuse-Argonne offensive which began Sept. 26 and lasted 4 7 days. One lone German plane returning from a raid had evidently one bomb left and on Oct. 15 seeing our barracks on a hilltop thought that it would be a good place to drop it. It landed on the field very close to the barracks and one corner of the building was torn off. No one hurt.

Manning the Boards to the Last

“On Oct. 30, our calls to Souilly, Widewing, did not go through. The lines were dead. Miss Banker writes in her story that fire had broken out. ‘Six or seven barracks went up like so many tinderboxes. The men and officers worked like mad, but a bucket brigade was powerless. The office was saved by the men and officers pouring pails of water on the roof but even then, for a while it looked as though it were doomed.’ Wires went down, the telephone line was out. Miss Banker and her operators worked on the boards to the very last. They were manning the ‘fighting lines’ which handled the calls of the officers actually directing Front Line operations.

“For this and the fact that she had been the first Chief Operator of the First Unit, Miss Banker was awarded the Distinguished Service Medal. She said: ‘Whatever glory may go with that medal, I have always felt belongs in large measure to the very small but very-brave and devoted group of First Army girls - Suzanne Prevost, Bertha Hunt, Adele Hoppock, Esther Fresnel, Helen Hill and Marie Lange’.

(Ed. Note: Mrs. Helen Hill Verdi and Mrs. Marie Lange Harris were with Mrs. Louis Le Breton Maxwell and the four other operators who received the honors due them at the Presidio Army Museum on Veterans Day.)

Mrs. Harris recalls working almost around-the-clock as the Meuse-Argonne offensive ground on. She also recalls sleeping in a stable with the horses to get away from the bed bugs upstairs. ‘I practically lived on raw onions and a little salt,’ she laughed. The officers in the surrounding units did their best, however, to smuggle what food they could lay their hands on to the operators. Among the best providers were Lieutenant Omar Bradley and Captain Mark Clark.)

“After the Armistice,” says Mrs. Maxwell, “our workload was just as heavy, calls all going to the ports. In February 1919, my sister and I were transferred to Paris where I was relief operator during the Peace Conference. Although it was wonderful to be in Paris in the spring, something had gone out, the task was accomplished. I began thinking of returning home, arriving in time perhaps to go to Summer School in June to make up lost credits at the University of California, and applied for my return. I was back in Berkeley at the end of May, the proud possessor of a Citation for Meritorious and Conspicuous Service in the American Expeditionary Forces signed by General Pershing.

“And so ended my great adventure, but not quite, for in 1920 I married that able and fine Sergeant John Maxwell and life continued to be a daily adventure for 57 years.” (Mr. Maxwell, a traffic engineer for Pacific Telephone, passed away in 1977.) Mme. Jeanne Le Breton said, “l have no sons to give to France, so I send her my Daughters.” General John J. Pershing said on completing an inspection: “Those girls are real soldiers!” Louise Le Breton Maxwell said: “Nous avons complete l’appel” (We got the message through!) Those were the days, my friends, when patriots were everywhere.

This was written by John Motheral, editor of the Fort Point Salvo, the newsletter of the Fort Point and Army Museum Association. Volume 4, number 6, December, 1979.

J'Ecoute: The Story of U.S. Army Signal Corps Telephone Operators in World War I

Two hundred twenty-three women volunteered as telephone operators and served in the American Expeditionary Forces in France, 1918-1920. They pose on top of the AT&T building in New York shortly before deployment to France.

The first unit of telephone operators posed for this Signal Corps photograph shortly after they arrived in France in March 1918. Grace Banker, Chief Telephone Operator, sitting center of first row.

Telephone operators assigned to Signal Corps Headquarters at Tours, France. These telephone operators held the rank of officer in the United States Army. They were the first women U.S. Army officers in non-nursing roles. This status was not recognized until 1978.

Telephone operators at the Frist Army Headquarters at Souilly, France. Bay Area women included are: Marie Lange Harris of San Francisco (2nd row, 2nd from left), Helen Hill Verdi of Berkeley (2nd row, 2nd from right).

General Pershing personally called for the formation of a Signal Corps telephone operator unit as part of his communications system in France during World War I. These American women were fluent in French.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operators line up for inspection and a parade in their honor, reviewed by AEF commander General John J. Pershing, in Tours, France.

U.S. Army Signal Corps women telephone operators in the long distance toll office at La Belle Epine, outside of the gates of Paris, France. Head operator Grace Banker standing background on left.

Telephone operators were on call 24 hours a day, 7 days a week, staffing the communications headquarters for the Army Signal Corps. They were required to be fluent in French to receive and dispatch calls to the French Army.

The American Telephone and Telegraph Company honored the U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operators on the front cover of their magazine, The Telephone Review, May 1918.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator Louise LeBreton. She was among the first women volunteers to sign up for service. (Photo 1918.)

Louise LeBreton attending the ceremony awarding her the U.S. Army Victory Medal for World War I. This ceremony was held on November 11, 1979, 61 years after the end of the war.

Louise LeBreton (right) and sister, Raymonde LeBreton, at exhibit honoring telephone operators at the Presidio Army Museum, November 11, 1979. Raymonde was a Quartermaster with the Service of Supply (SOS) Department of the American Expeditionary Forces (AEF).

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator Maude E. Johnson Webster.

U.S. Army identity papers of Maude E. Johnson. It shows that she was 21 when she volunteered for service.

Maude E. Johnson Webster standing in front of a U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator’s uniform, at the Presidio Army Museum opening of an exhibit honoring her and her comrades, November 11, 1979.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator with non-regulation beret.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operators were not granted full status as soldiers in the U.S. Army until after November 1978, when a bill was passed by Congress. It took 60 years for them to get full recognition.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator Helen Hill (Verdi; left, in doorway) with fiancé (on right in overcoat), Captain Mark Clark. Mark Clark became commander of the U.S. Army in Italy during World War II and, later, in Korea. (France 1918.)

Helen Hill (Verdi) at the Presidio Army Museum after she was given her World War I Victory Medal, November 11, 1979, at the opening of the J’Ecoute exhibit. She stands in front of the actual uniform she wore in France.

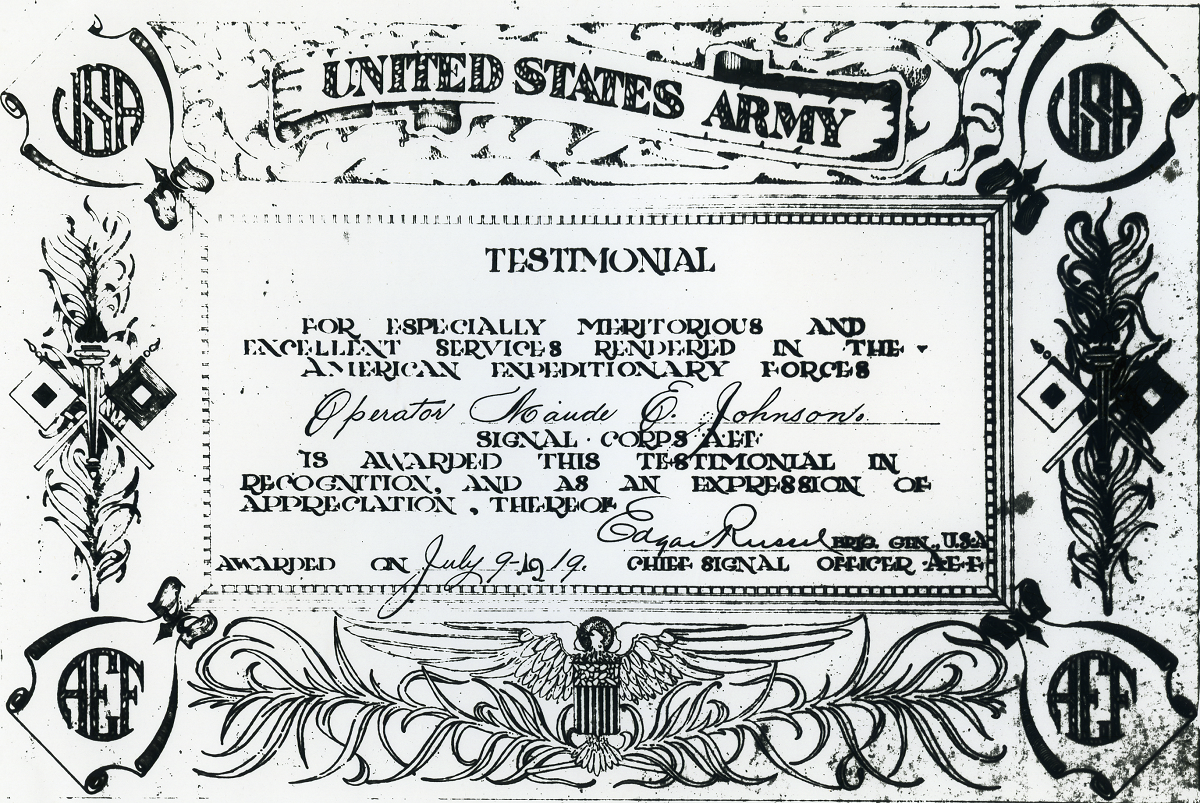

Certificate awarded to Maude E. Johnson for “especially meritorious and excellent services rendered in the American Expeditionary Forces.” Operators received these certificates in lieu of promised official service discharge papers.

Operators who received their World War I Victory Medals at the Presidio Army Museum, November 11, 1979. This was the official opening of an exhibit honoring them, entitled J’Ecoute.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operators (L to R), Mrs. Bertha Plamandon Dubsky, Cordelia Dupuis Davis, Louise LeBreton Maxwell, Helen Hill Verdi, Marie Lange Harris, Maude Johnson Webster, Raymonde LeBreton Galet.

Operators pose in front of an authentic World War I era telephone switchboard. These veterans were reunited for the first time in more than 60 years.

Ceremony in front of the Presidio Army Museum honoring and recognizing World War I U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operators, November 11, 1979.

Colonel George Pappas, President of the Company of Military Historians, awards U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator Louise LeBreton Maxwell her long-awaited World War I Victory Medal, November 11, 1979.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator Mrs. Bertha Plamandon Dubsky receives her World War I Victory Medal at Presidio Army Museum ceremony, November 11, 1979.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator Marie Lange Harris receives her World War I Victory Medal 61 years after the Armistice of World War I, November 11, 1979.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator Maude Johnson Webster receives her World War I Victory Medal at long last, November 11, 1979.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator Cordelia Dupuis Davis receives World War I Victory medal on the 61st anniversary of the Armistice in France, November 11, 1979. Ms. Davis served in the occupation of Germany in 1919.

The families of the telephone operators, including children and grandchildren, attended the ceremony and the opening of the exhibit, J’Ecoute.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator Helen Hill Verdi receives World War I Victory Medal at Presidio Army Museum ceremony, November 11, 1979.

Helen Hill Verdi was among the original volunteers for the U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operators detachment. She served through the Armistice.

Major General Sniffen, Sixth U.S. Army, and Eric Saul, Director/Curator of the Presidio Army Museum, at official ribbon cutting ceremony for the J’Ecoute exhibit, November 11, 1979.

World War I telephone operators (L to R): Marie Lange Harris, Bertha Plamandon Dubsky, Raymonde LeBreton Galet, Louise LeBreton Maxwell, Cordelia Dupuis Davis, and Helen Hill Verdi.

World War I telephone operators (L to R): Marie Lange Harris, Bertha Plamandon Dubsky, Raymonde LeBreton Galet, Louise LeBreton Maxwell, Cordelia Dupuis Davis, and Helen Hill Verdi at J’Ecoute exhibit opening.

World War I telephone operators Marie Lange Harris, Louise LeBreton Maxwell, Helen Hill Verdi, and Maude Johnson Webster at Sixth Army Headquarters, Presidio of San Francisco.

Sisters in arms Raymond LeBreton Galet (left) and Louise LeBreton Maxwell. Louise met her future husband, a Signal Corps officer, in France. Raymonde served in the Quartermaster Department of the U.S. Army in France.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator Bertha Plamandon Dubsky at J’Ecoute exhibit opening, November 11, 1979.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator Cordelia Dupuis Davis. After serving in France, she volunteered to serve in the U.S. Army of Occupation in Germany.

U.S. Army Signal Corps telephone operator Maude Johnson Webster. Maude was one of the original 223 “Hello Girls.”

Museum Director Eric Saul at J’Ecoute opening ceremony. This was the first in a series of exhibits honoring unique units in the U.S. Army. Other exhibits highlighted the history of African American and Japanese American soldiers.

Eric Saul was the Director of the Presidio Museum from 1977 to 1986.

Two hundred twenty-three women served as telephone operators in the U.S. Army Signal Corps during World War I.

These were the first women to serve as soldiers in the U.S. Army, specifically in non-nursing roles.

The Army desperately needed bilingual telephone operators to staff the switchboards at various headquarters for the American Expeditionary Forces in France. Few men were found who were capable of this demanding job, so General Pershing called for women to fill these vital wartime positions.

They were enlisted in the Army as official soldiers and given the status of company grade officers. They were sworn into the Army under the Articles of War. They wore regulation U.S. Army uniforms and were subject to Army regulations.

This unique unit was comprised of French-speaking American citizens. They trained in their specialized skill at the AT&T headquarters in Manhattan and at the Signal Corps training facility at Camp Franklin, later Fort Meade, in Maryland.

They served with honor and distinction close to the front lines after they arrived in France in March 1918. They were close enough to the front to be in danger of being shelled by the Germany army. They served in Paris, Chaumont, and numerous other French locations. They also served in Great Britain in London, Southampton, and Winchester. Their service was a vital link between the American and French armies. Their work contributed to the Allied victory over Germany. Several of the women volunteered and served as operators in France after the war and in the Army of Occupation in Germany through 1920.

Chief Telephone Operator Grace Banker received the U.S. Army Distinguished Service Medal for her services. This is the third highest medal that the Army can bestow.

At the conclusion of their service, the Signal Corps telephone operators were given certificates of service rather than the honorable discharge to which U.S. Army soldiers are entitled. To their surprise, they were told that they never, in fact, had official status as soldiers. The Army told them that they were civilian employees of the military. This was contrary to all that they were told at the beginning of the war.

With the exception of Grace Banker, they received no honorable discharges, no campaign medals or victory ribbons for their service overseas. They did not receive the bonus pay that was given to other soldiers in the AEF, and received no pensions or Veterans Administration benefits.

These brave and adventurous women who fought for their country so honorably took up the cause of their being recognized. The “Hello Girls,” as they were called at the time, fought for 60 years to get official recognition for their service as soldiers in the U.S. Army. A bill to recognize the telephone operators was passed by Congress in November 1977 and was signed into law by President Jimmy Carter.

On August 28, 1979, several of the “Hello Girls” were given their discharge papers at Fort Lawton in Seattle.

After reading of their recognition by Congress, I decided that I would seek out surviving women telephone officers for a special ceremony at the Presidio of San Francisco.

After a search, we discovered that there were seven surviving members of the women’s Signal Corps telephone operators living in the San Francisco Bay Area. Among them were Mrs. Bertha Plamandon Dubsky, Cordelia Dupuis Davis, Louise LeBreton Maxwell, Helen Hill Verdi, Marie Lange Harris, Maude Johnson Webster, and Raymonde LeBreton Galet (Quartermaster Department).

We conducted oral histories with a number of the women and collected photographs and other pieces of precious memorabilia of their wartime service. We curated an exhibit entitled, J’Ecoute (I am Listening; Number Please): The Story of U.S. Army Signal Corps Telephone Operators in World War I.

The Woman’s Overseas Service League (WOSL), a woman’s veterans organization, had been holding the papers of former telephone operator Mildred Lewis. These papers were donated to the museum and incorporated into the exhibit. The day before we opened the exhibit, one of our museum supporters donated Mildred Lewis’ overseas service cap, which he had serendipitously discovered at an antiques show.

The exhibit opened on November 11, 1979, the 61st anniversary of the end of World War I. At the ceremony, we gave each of the surviving telephone operators their long-deserved World War I Victory Medal.

Many of the women had not seen each other since the end of the war. Their families and friends were in attendance.

The pride in their service, and in receiving recognition at long last, can be seen on the faces of the World War I telephone operators in the photographs of the ceremony.

The World War I telephone operators set the standard of excellence for women in the military in future generations. The Woman’s Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC) was established in May 1942. The occupation of telephone operator was among the first specialties authorized for women in the service. The Woman’s Army Corps (WAC) was established in 1943, allowing full status for women in the United States Army.

A brand new book just came out honoring the telephone operators, which I would highly recommend reading. It is a thoughtful and comprehensive book on the history of the “Hello Girls.” It is: Cobbs, Elizabeth (2017). The Hello Girls: America’s First Women Soldiers. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674971477.

I’d like to take this opportunity to thank two of the officers who helped and supported the museum and this exhibit. They are Colonel F. Whitney Hall, Commander of the Presidio of San Francisco, and Colonel Donald R. Sims, Commander of the Department of Plans, Training and Security (DPTSEC).

Eric Saul

Director/Curator

Presidio Army Museum

See articles below